Unsung Heroes: The Vital Role of Managers in Data Teams

Exploring the impact of leadership in building successful data teams

TL;DR

Managing people, particularly in data organizations, is a challenging task that involves planning, mentoring, giving feedback, and engaging with stakeholders. It is well known that great leaders exhibit emotional intelligence and other desirable traits, but data managers must also be hands-on, show considerable business and technical expertise, and be great communicators and sales people. Transitioning from an individual contributor to a managerial role has its challenges but can also be highly rewarding. Continuous feedback is crucial for to become a better manager. The best companies have robust management layers and processes, and the best data-driven companies have great data managers. In this post, I share a Google sheet for self-assessment, and a guide for hiring managers.

Introduction

In the previous post I discussed which data organization – centralized or decentralized – is better for your company, and mentioned in passing, the importance of having a strong management layer. This is true independently of which org structure you choose, but it’s certainly critical if you decide to build a decentralized team.

Data science is still in its infancy as a discipline, with many companies only starting their journey towards maturity. Individual contributors (ICs) are still in high demand, so many hiring managers struggle finding the right talent for their company. But if finding good ICs is hard, finding the right data managers might seem to be an almost impossible task.

In this post I want to discuss why managers are so important in a data organization, and what it takes to be a great manager.

Why are data managers so important?

In general, managers play an important role regardless of their specific function. They must plan, execute and evaluate their team’s objectives, ensure cross-team alignment, motivate the team members, provide feedback and prioritize tasks. They must also communicate the state of the company to the team, and ensure that the leadership team’s culture (vision, methods and practices) are applied across the board. Being a manager is hard.

On top of that, a data manager must ensure that the standards and practices are maintained and improved, and provide technical and business mentorship the team members. They must be strategic, and create, maintain and discuss a backlog of projects with their stakeholders.

Effective data managers ensure that an organization operates in a data-driven manner, while also maintaining a high level of technical expertise and motivation.

My own personal story: the path to becoming a great manager never ends

Let me start with my own personal story. After getting my Ph.D, I first worked for a central bank doing research, and finally transitioned into the industry. In my first role, I had to manage a team of three individual contributors, but in reality my job was closer to an IC than a manager. But I wasn’t a “manager”. I did mentor my team , but I lacked all of the relevant skills. Moreover, I wasn’t really interested in becoming a proper manager. I loved coding and coming up with solutions to interesting and relevant problems.

After three years in that role, I felt it was time to move on and got two job offers: one was as an IC for a cool tech startup, and the other was to create and lead the “Big Data” team for a large corporation. It was a really hard decision because I loved being an IC, and I didn’t want to deal with company politics. Against all odds, I ended up joining the second company, knowing nothing about managing teams and handling internal politics. And this was a very political company: the perfect recipe for failure. But I loved it, and learned a lot about handling politics and managing teams (this is not to say I was a great leader, actually it was quite the opposite).

At the time, I read every single piece on management practices that outlets like the Harvard Business Review had, but in reality, I only learned to become a good manager when I saw good managers in action. My next role was at a great company, so they also had a very strong and well-structured management layer. I’d venture that all great companies have very strong management, at all levels. In my next role I started applying everything I learned, and continued to learn with every mistake I made (and there were many). Becoming a great manager is a life-long adventure.

Great companies also have great managers and processes that ensure that this is the case

What does the management literature say about it?

Managers are so important to companies, that the academic literature has provided quite a bit of advice on how to become good at it. This literature teaches about emotional intelligence, ownership and accountability. You’ll also learn about the different leadership styles (coercive, authoritative, affiliative, democratic and the like), the archetypes of leadership, and the most common mistakes the leaders make. Being an economist, I really enjoyed going through the behavioral economics literature, and what they have to say about human motivation. And the list keeps going.

Don’t get me wrong, I think this literature is mostly right about all of this (at least directionally speaking). Being emotionally intelligent is important, even though there are great leaders that lacked these characteristics (think Steve Jobs and Elon Musk). Nonetheless, I do think that becoming more self-aware, learning to self-manage oneself, being socially aware (empathy and organization awareness), and improving your social skills is critical for success. And this is especially true for the technical individuals, who often lack some of these traits.

Principles for being a good data manager: what is success?

Let’s use a principles-based approach to find the traits that great data managers have. I like to start by defining success and then reverse engineer the problem. If you’re familiar with the management literature, you’ll see that I take a lot from it, but I also depart from it when necessary.

What is success for a manager? As usual, everything boils down to creating value: a manager will be successful if they can create high value for their team, over time, in a sustainable way, and let the company know of it. This must also be aligned with the company’s values and culture, and with the data team vision and practices.

A manager will be successful if they can create high value for their team, over time, in a sustainable way, and let the company know of it.

Figure 0 shows the main ingredients for success. As a manager, you’re first and foremost responsible for your team’s output and value (1). Naturally, these terms are not synonymous: your team may generate large volumes of output, but produce little to no value. To maximize value you must mentor, motivate, prioritize projects, plan goals and evaluate performance, communicate clearly (your expectations, the rules for evaluation and the company’s main messages and current state), as well as be humane and compassionate.

Since you don’t work in isolation, you are also responsible for managing the relationship with your business stakeholders, ensuring that the data science capabilities are used efficiently, prioritizing high-value projects that are attainable in the short- and medium- terms, aligning expectations and communicating ETAs and results (2). You must be proactive, and constantly sell the data-driven approach that may be foreign to your stakeholders. You must also be resilient, and learn to keep going, even though your proposals may keep getting rejecting.

You must also manage up (3), and communicate effectively with your manager. This will allow you to get your ideas and projects approved, sell your team’s work and thus get more resources, learn what is the current state of the company, and get (and provide) feedback. An important part of managing up is to communicate with your manager’s peers too, and this is more important as you become more senior.

Working with your peers (4), allows you to share best practices and reduce redundancies. Finally, alignment with the overall company is critical (5). The main advantage of being a manager, is that you get a 360 view of the current state of the company, its current needs, strategic projects, and future plans. Developing this strategic view can take the data team, you, and your own team very far.

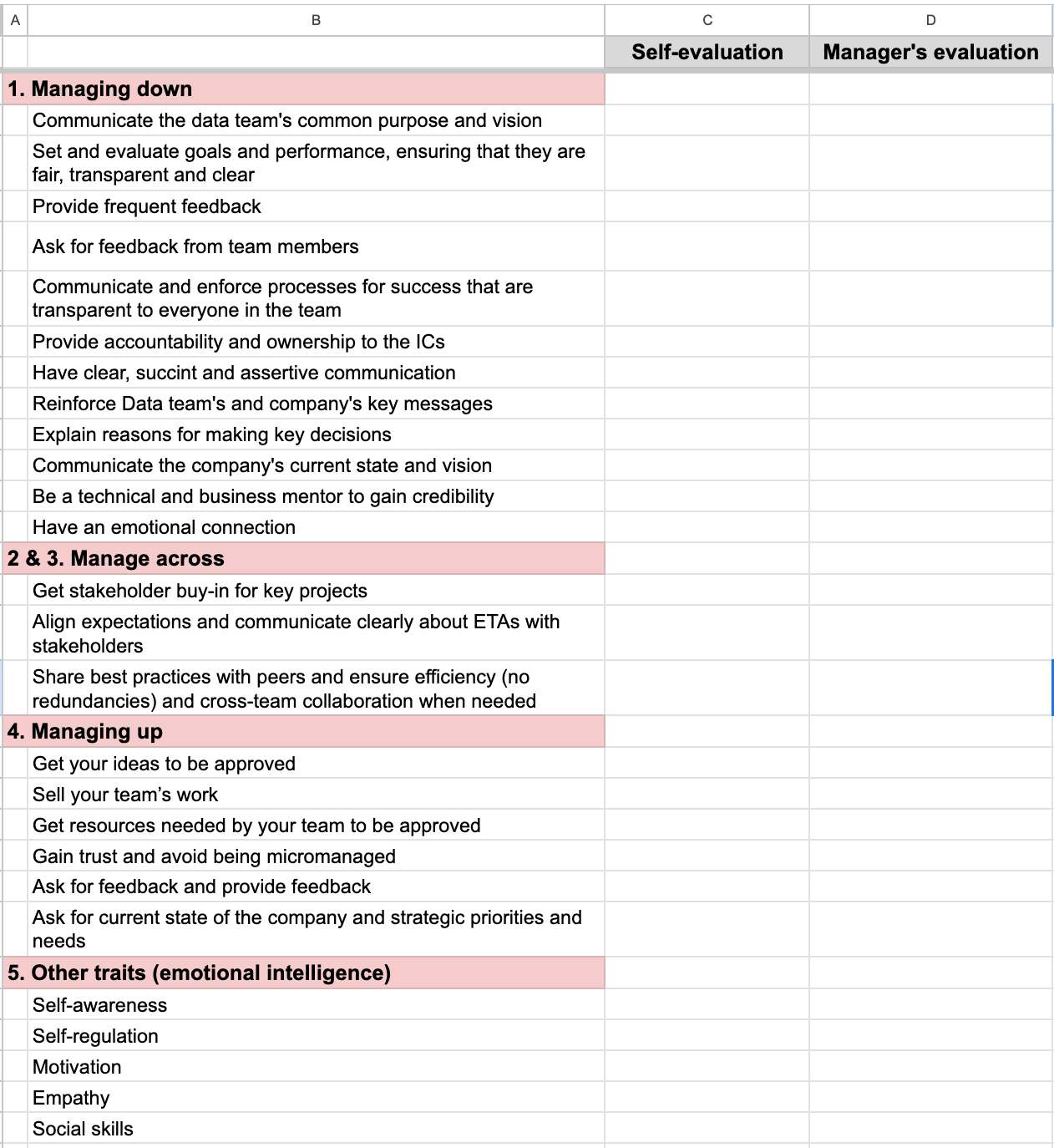

I hope this explains why being a manager is extremely hard. To make this operational, I usually use an evaluation questionnaire that goes into more detail on each of these dimensions, and can be tracked over time (Figure 1). It comes as a Google Sheet that can be copied and adjusted as needed. Note that it’s not expected that your managers (or you) will be perfect. All leaders have flaws, but this provides enough structure to align expectations and a path for your improvement as a manager.

Data managers should be hands-on

Technical managers should be hands-on. I’ve seen data managers that think that their role is to arrange meetings, facilitate their team’s work, and unblock problems. Naturally, these are required traits too. But you should know the data as well as your team members, and the only way to do it is by being hands-on.

What does it mean to be hands-on? It really varies, but it’s important to lead by example. I find it very hard for a manager to provide feedback on a machine learning model, advanced analytics project, dashboard or report, or data engineering task, if they are not familiar with the intricacies and details of these elements. That’s why I always look for managers that transitioned from being great ICs, rather than looking for the more common generalist manager.

You should know the data as well as your team members, and the only way to do it is being hands on. Aim at leading by example.

Data managers as ambassadors of the data-driven method

Adopting a data-driven approach to decision-making is not an instinctive process for many individuals. It often requires a conscious effort and a shift in mindset. Furthermore, it requires extensive training. Data managers play a key role in helping a company transition to data-driven territory, and as such, they act as ambassadors and evangelists of the data-driven method. They must also ensure that their team members act accordingly.

Becoming a data evangelist requires outstanding sales skills and perseverance. But you also need to live up to the standard. You can’t be a credible evangelist if you don’t know the techniques thoroughly, but you must also know the business if you want to be trusted by your stakeholders.

Transitioning from an IC role to management

ICs tend to love what they do, so most mature companies provide career paths that ensure that their salary and responsibilities can grow, as an IC or a manager. However, in many companies, these aspects can only grow if you transition to a managerial role. This can, unfortunately, lead to the demoralization of your best ICs, who may then choose to leave for another company.

This said, becoming a manager enhances your ability to make an impact, as you gain a more strategic view of the company and it becomes easier to be involved in key decision-making processes (and you would want your team to improve these processes). The downside is that you will have less time to work on specific projects, but if you’re hands-on, you’ll find the time. Moreover, you can mentor ICs, helping them to improve not only as data scientists but often also as individuals.

Becoming a better manager: ask for feedback

Being a manager is challenging, and you can expect this to continue as your career progresses. Moreover, different skills are more effective in different company cultures, so managers must also develop a strong degree of adaptability.

I’ve found that the above questionnaire generally works well as a North Star to becoming a better manager, but naturally, it shouldn’t be used as the ground truth for your career. Adapt it as needed, or discard parts as you feel appropriate.

Having different managers yourself is also quite beneficial, since you can experience different management styles, and decide what works for you or not. It’s important that your management style works well for you. When I was reading all of the management literature, I wasn’t really ready for most of it, and it felt like I was trying to become someone I couldn’t be.

And it also requires getting a significant amount of feedback. I always tell the story when I got the harshest feedback in my career from the company’s CEO, who said something along the lines, “Daniel, from what I see, you are the worst leader in the company”. That feedback, along with the rest of the conversation, helped me identify what I was doing wrong, and to this day, I keep working on some of those issues. Remember, it is a long-term game. Listen to your peers, to your manager and their peers, and listen to your team members.

Constructive feedback can work wonders for your career.

Building a strong management layer

As I said, the best companies have very strong managers, and processes that ensure that this is maintained and replicated across the organization. There’s so much you can do by yourself, but if it’s not part of the culture, or HR isn’t really focusing on this, it’s unlikely that you’ll succeed. Building strong management is a company-wide initiative.

When I first implemented the questionnaire with my managers, it took some time for it to take effect. However, I was eventually able to introduce some structure into their feedback and career path discussions, which proved to be very beneficial. Furthermore, the ICs were aware that I was having these structured conversations, so they were also motivated to have their own versions of it (I’ll write about it in another post). I was also fortunate that HR was aligned with it, and it somewhat became the best practice within the company.

Guide for hiring managers

Because of the underlying uncertainty, hiring is always a challenging process. You have to consider both false positives (hiring someone who isn’t a good fit for the job, team, or company) and false negatives (not hiring someone who would have been a good fit). I’ve made both of these mistakes several times, so let’s discuss this now.

False positives

Not so long ago, I was having a really hard time finding the right person for a manager’s role, and HR was becoming impatient about it (“Daniel, you need to hire someone or you can lose the position”).1 I ended up lowering the bar and I paid the price several months later, by having to let that person go (after providing multiple rounds of constructive feedback). I had to micromanage that person, and effectively play the manager’s role with that team.

The mistake I made during the interview process, was putting a low enough weight on being hands-on and on their ability to provide business and technical mentorship, and those are critical skills that data managers should have.

On another occasion, I provided a high-performing IC with the opportunity to become a manager, but it turned out to be too early for them. Their communication skills were not the best, and their understanding of the business was also lacking. This is a tougher error to accept as a manager, since hiring from within usually reduces the uncertainty on a candidate’s qualifications. But good ICs don’t always make good managers, at least in the short-term (I’m convinced that everyone can become a great manager), and companies are run in the ultra-short term and many times you just can’t wait to get the results.

False negatives

False negatives arise most frequently because companies (and people) are generally terrible at structuring interviews. Of course, it can also be that the interviewee had a bad day, but most likely you, the interviewer, did something wrong.

Great companies also have really well-structured hiring processes.

In markets abundant with qualified candidates, such as Silicon Valley, the cost of a false positive is relatively low. However, in other locations, this can be quite expensive. Below is a list of strategies that have proven effective for me. Please feel free to leave your comments so that I, and others, can learn and continue to refine our hiring processes.

Work on the job description (JD): it’s key that you know what you need from the outset, and identify the minimum qualifications needed. But be honest: there are many JDs that ask for everything in the world; in my opinion, this is just a sign of laziness (or the fact that HR can’t do it without your expert help and opinion). If you think that being a mentor and hands-on is key, be explicit about it and ensure that you test for this during the interview.

Structure and prepare the interviews: prepare for the interview in advance. Read the CV, prepare the questions, think about use cases that can be used as examples, and ensure that your communication is clear. You can’t expect a candidate to perform well, if you’re all over the place during the interview. Many people transition directly from a meeting to an interview, without even reviewing the candidate’s CV.

Prepare your interview to separate signal from error: there are many things that can go wrong with an interview, but the best questions are designed to separate signal from error. A common technique is asking about the candidate’s specific experience. For example: “Can you describe a situation where you had a large amount of data but needed to extract relevant insights? What was your approach, what tools did you use, and what were the results?” This also works great when assessing a candidate’s business and technical expertise, and how hands-on they are, but also to assess their “softer” management skills. For instance, I always ask about some instance where they had to deal with an uncomfortable situation with business stakeholders, a team member, and their own manager. If you’ve never experienced this, you haven’t been a manager.

Be as honest as possible about the role, the company and the hiring manager: hiring is a two-sided match. You want the candidate to work for you, but you also need you, and the company, to work for them. Provide as much information as possible, to ensure that this is a good match for both parties. For instance, I have a very assertive communication style, which some individuals may find difficult to tolerate. When I interview someone as a hiring manager, I strive to be as authentic as possible, without any sugar-coating.

Leave time for questions: since hiring is a two-sided match, ensure that you leave time for questions. Furthermore, their questions also provide information about them. If they don’t ask questions, it can be that they’re not interested, they’re not senior enough (that’s not necessarily bad), or they didn’t prepare. Practice on your listening skills (which are also very important as a manager).

Summing up

Becoming a manager is hard, but it’s harder to become a good one. But great managers make companies great, and this is especially true for data organizations. I’d love to learn about your experience, so please leave comments!

Hiring requires you to be strategic: budgets are not fixed, so many times, if you don’t execute them, you just lose them.